How We Learnt – An Introduction to Recent Education Psychology Findings

How We Learnt – An Introduction to Recent Education Psychology Findings

Author: Prof Ng Tai Kai

I. Cognitive and Non-cognitive Skills

A long-standing question: What makes students successful?

This is one of the long-time focuses of education research. To answer this question, we must know what the essential skills/abilities a student must acquire to be successful, and whether we can design appropriate tests and training to detect/nurture these skills/abilities. A well-known example in this direction is the IQ test, which is a general cognitive-ability test designed to identify students with the best potential to become successful adults.

The power and limitation of the IQ test have been discussed in my previous article (Introduction to Gifted Education). In summary, it is found that although IQ is a good indicator of the overall potential of success, there are other abilities, not measured by the IQ test that strongly affect the success of human beings. A similar result is also obtained if we replace the IQ test by public examination scores.

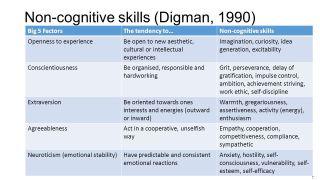

Starting from the late 20th century, it is gradually understood that besides the cognitive abilities (measured by IQ or other general ability tests), our students also need other skills to be successful. These skills are collectively called non-cognitive, or ‘soft’ skills. Broadly speaking, cognitive skill reflects the ability of students to learn different knowledge efficiently, and non-cognitive skills are skills that enable individuals to respond properly and work with others in the community. The systematic study of non-cognitive skills started in the latter part of the 20th century. For example, the table below presents a classification of non-cognitive skills by Digman (1990).

The non-cognitive skills often reflect our deep-rooted mindset and are different in nature compared with cognitive skills. Nowadays, it is understood that the human mind can be thought of as composed of two parts: a ’thinking’ part and a ’feeling’ part (see ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’ by Kahneman):

The human brain was built from the bottom up:

- The brainstem is responsible for all our basic necessary functions (breathing, eating, sleeping).

- The limbic system built on the brainstem, and this system is responsible for our (fast) responses and emotions. It gave us the basic ability to learn and remember, which allowed us to adapt to new environments.

- Then our neocortex formed on top of the limbic system, and this is our rational (slow) mind. It gives us cognitive abilities as well as the ability to choose how we respond to our emotions, reflect on ourselves, and feel empathy for others.

Our feeling mind (limbic system) is associative, categorical, absolutist, and individual -- and it reacts to information before our thinking mind (neocortex) even gets all the information and has an opportunity to weigh out the best action. We cannot change our fast, feeling mind, which is built at birth, but our thinking mind can be trained to respond to, and control our feelings. This is the neurological foundation behind the cognitive and non-cognitive skills.

II. Affective Education

To nurture the ‘feeling’ mind so that students can learn effectively at school is the subject of affective education.Parents send their children to school for them to learn Maths, Science and English (cognitive skills and knowledge). Eventually, educators and psychologists realised that teaching students about these subjects alone is not enough for them to perform well in school. Many students cannot focus on their studies not because of lesser cognitive abilities, but because they were troubled by boring classroom or problems at home. Many students tagged as brilliant might flunk their classes because of a lack of learning motivation. Problems like these have led to the birth of affective education.

Affective education is concerned with the beliefs, feelings, and attitudes of students. At the Individual level, educators must take care of the individual needs of students. For example, how to encourage teens with low learning motivation or is deficient in say, communication skills; deficiency in communication skills might hinder students from making friends with their classmates and may turn them into bullies or get bullied. Hence, at this level, a teacher needs to promote emotional literacy and a self-motivated mindset. A teacher may do this by encouraging students to build their own study practices or to find out the many different career tracks they can take in the future. When students have goals and are encouraged to achieve them, they will feel better about themselves, and when they do, their school performance also becomes better. They will also have better relationships with other students.

At the Group level, the focus is given to the interpersonal relationships among students. Interpersonal intelligence must be fostered in the school environment because social skills are necessary for a person to function well in life. With affective education in mind, teachers make students participate in group activities so they will learn to respect other people's interests/opinions and make friends.

The last level of affective education is the Institution level. It is not enough to cultivate relationships among students in classrooms. The school environment - the guidance counsellors, principals, teachers, and other staff - must also build an atmosphere of concern to students. Guidance and support must always be available to students.

Unfortunately, the design of the Hong Kong school curriculum did not pay much attention to the affective needs of students in the past. With the high student depression and suicide rate Hong Kong schools are facing nowadays, it is gradually understood that affective education is an indispensable component of education and is now a direction the Hong Kong (school) education system is moving towards.

It should be emphasised that affective education is not limited to students with study problems. It is now understood that the success of a student depends very strongly on his/her affective mindset. In his study of gifted education, Joseph Renzulli proposed in his famous 3-Ring Model that Creativity and Task Commitment are as important as Intelligence (the ability measured by IQ) for the success of gifted students. This is the first time the importance of a student mindset is formally proposed as important ingredients in nurturing (gifted) students. Nowadays, much work has been done in this direction. For example, Carol Dweck’s emphasis on Growth Mindset and Angela Duckworth’s work on Grit are well-known examples of studying what are the required affective mindsets for students to succeed. There are also more systematic studies on how non-cognitive developments of students may impact their learning in general. The HKAGE is the first educational organisation in Hong Kong bringing affective education as a fundamental component in its gifted education programmes.

In my next (final) article, I shall discuss how we can bring together our understandings on the importance of non-cognitive skills (or affective education) and the need for our future generation to acquire the so-called 21st century competencies and STEM in the future development of the HKAGE.